Sliabh Beagh

Where the counties of Monaghan, Fermanagh and Tyrone meet

Eamonn Murray contributed weekly articles for ‘The Northern Standard’ newspaper during the 1930s, whcih provide a respository of regional information.

'I am watching the death of Irish music in our mountain, and I know not how to check its passing'. (Eamonn Murray, 1947)

Straddling the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, the Sliabh Beagh region of counties Monaghan and Fermanagh possesses a long-standing musical tradition, albeit one which is often overlooked at a national level. Despite this absence, glimpses of the region’s musical heritage may be found in a variety of sources, including, among others, the newspaper columns of Sliabh Beagh musician and cultural activist Eamonn Murray (1912-1966). Centrally involved in the early Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann movement, Murray’s columns – contributed to The Northern Standard newspaper during the 1930s and 40s – provide a valuable insight into the traditional music practices of the Sliabh Beagh area. While demonstrating the continued presence of the region’s local music traditions, Murray’s columns also highlight the dwindling status of traditional music in the area during this period.

In Murray’s opinion, the music traditions of Sliabh Beagh region – an area he sometimes referred to as ‘Our Dear Dark Mountain with the Sky over it’ – were in retreat. Confronted by the progressive development of mass media and an ever- expanding array of musical alternatives, the local musical tradition was challenged by new and exciting traditional styles of playing, repertoires and techniques. Gramophone records and radio performances of virtuoso players were imitated, often to the finest detail, with local tunes and settings being set aside. Witnessing the impact of such pressures on the region’s musical traditions, Murray implored the area’s traditional musicians not to allow mass media “to influence them away from their own distinctive style of playing, or to push the native tradition and repertoire into the background.” (Murray, 1961).

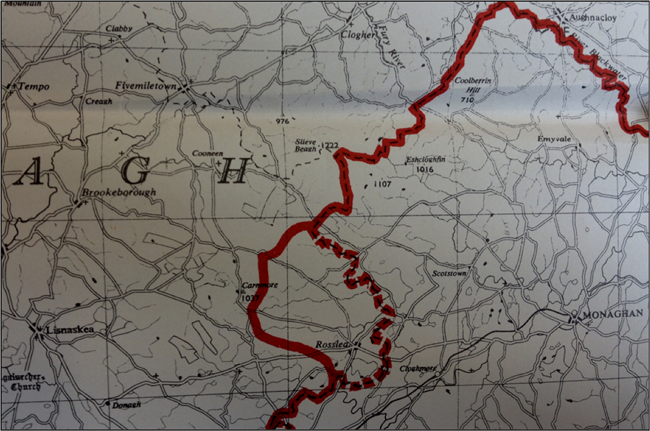

Faced by a relentless tide of economic, social and political change, the social conditions which had fostered the region’s musical traditions were also undergoing considerable transformation. The enactment of the Public Dance Halls Act (1935), a draconian attempt to control public morality, modified the nature of social gatherings throughout rural Ireland, moving dances from the traditional settings of kitchens, barns and crossroads towards organised dances in larger halls. In the Sliabh Beagh region, the social landscape was further altered by the creation of a national border dissecting the area. Ignoring recommendations by the Boundary Commission (established under Article XII of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty) that the economic and geographic integrity of the Sliabh Beagh area of Monaghan / Fermanagh be maintained, the establishment of a border through the region distorted and destroyed both economic and social links which previously traversed the border region. Exacerbating an already difficult economic situation created by both the international economic depression and an Economic War with Britain, this fracturing of the region’s natural geographic and economic hinterland also contributed to the depopulation of the area. Indeed, during the years 1911 until 1966 (a period largely overlapping with Eamonn Murray’s own lifespan) the population of both Monaghan and Fermanagh declined substantially: Monaghan from 71,400 to an all-time low of 45,700 and Fermanagh from 61,800 to 49,800 inhabitants.

Old songs are no longer told, old tunes but seldom played, and the old songs are dying. These have no place in our daily lives, are not sufficiently cosmopolotian for our liking.

Old songs are no longer told, old tunes but seldom played, and the old songs are dying. These have no place in our daily lives, are not sufficiently cosmopolotian for our liking.